The other day I had the rare pleasure of playing with The Mindset: Sean Hogan’s deliciously evocative deck of cards commissioned by Desktop Magazine, with the brief to create something that can modify people’s behaviour. Some cards show a gradation of colour; others, a pattern; others, a geometric shape; others, a contrast of hues; others, a single line. In playing with them for a couple of hours, I was left with the sensation of a highly animated mind – a brain even more curious about its own workings.

Constructive disruption is the deliberate unsettling of the way you’re most comfortable thinking or working. It sets into play various elements that invite your response: a problem to solve, a game to finish, a randomness to explain. In doing so, it allows you to create your own framework for rendering palpable the workings of your mind as it tries to create order and meaning.

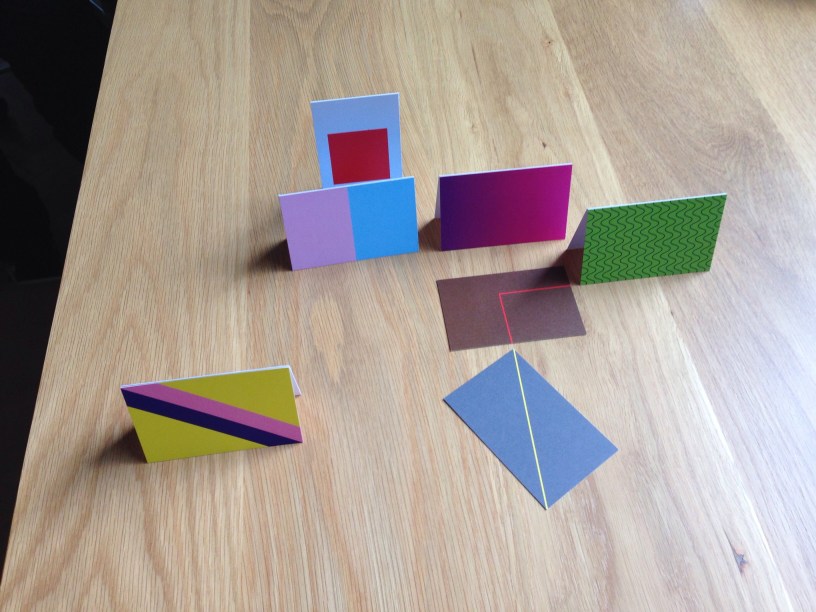

The Mindset can be used however you like. Wisely, Sean prescribes a starting point: select a dozen cards at random and compose them however you like. It’s much harder than it sounds. What happens when you choose one card and not an other? Why do these two seem complementary? Why do those two clash? Why did I move that there? This sensation of liking one card over another, how did it develop without a context for making that preference? Why do I like this pattern and not that one? As you work, you feel the brain creating order, and you watch the hands creating order, and you sense these as distinct processes. You perceive the workings of your instincts.

You perceive the moment of a decision – the moment from which things can become otherwise – and you perceive it as a moment of recognition, rather than a moment in time that’s quickly replaced by another as the decision is made.

The brain is a complex beast, always working on a number of things at a time – more than you can count. What happens when you make a slip of the tongue? What associations do you unleash? Isn’t it fascinating to draw the connection out deliberately, and unpack those links that were there all along?

And have you experienced the Cocktail Party Phenomenon, where you can’t hear what the people chatting next to you are saying, until the moment someone utters something salient or ribald or even just your name – and all of a sudden you realise that part of you was listening all the time because now your attention has diverted itself to their conversation? We like to think of it as being just the one brain and the one consciousness, but the reality isn’t that simple.

As a woman with a faulty* brain, I am both fascinated and terrified when I read back on how epilepsy and similar conditions were treated in decades past. When the corpus callosum that joins the two hemispheres was severed surgically to prevent the chain reaction of electrical activity that is the epileptic seizure, the left and the bright brain were separated – and amazingly, could perform functions independently of one another. Roger Wolcott Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga asked such patients in controlled conditions a set of questions, who would grasp an object to indicate their answer, while verbalising a contradictory response at the same time. Sperry and Gazzaniga’s Nobel-Prize-winning work demonstrated how compartmentalised the brain is; we owe our common use of the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ brain largely to their work.

I see constructive disruption as essential to the creative process, but essential also to any work that requires strategic development and complex management. To approach new problems through known methods is a way to certain conservatism in thinking and in process. To innovate, we need to challenge not only what we think but also the way we think. Consciousness has all sorts of ways to reward us for remaining in the groove of well-worn paths: the joy of repetition. It’s challenging but also rewarding to free the brain of that singularity.

Because my brain is faulty, and because I speak several languages, my experience of consciousness is not one of consistency nor of a singular focus – nor indeed of a singular consciousness. Always a multiplicity. There are three kinds of moments in my everyday life when I experience an unexpected jarring of brain activity: the scrambling that comes with migraine onset or exposure to fluorescent lights; rare moments of phenomenally rapid mental processing; the mismatch of language when I stumble for the right word. I experience a jarring, and yet there is also a fascination, a consciousness that my brain is undergoing a structural disjunction – an awareness that there are competing structures. Such experiences can be quite distressing and painful, and – depending on where I am – the first can be quite dangerous. Constructive disruption strengthens my recovery from those jarring moments, but more importantly, it’s generative, its creative and it’s a joy – what Sean calls “a holiday for the mind.”

Sean Hogan is a graphic designer and typographer whose work you already know as the man behind the Federation Square identity and signage. With The Mindset, Sean applies his expertise in design for guiding behaviour in a new way. I’m particularly enamoured of his Untitled Geometries 2015 series which combine signification with composition in the form of abstracted semaphore.

As Sean and I speak – our conversation traversing such far-flung topics as the politics of signage, the role of play in education, and the remarkably complex mathematico-geometric diagrams of his grandfather who survived Auschwitz – my hands can’t stop working, constantly rearranging my grid of twelve cards into new configurations, new compositions. Now telling a story of contrasts, now of lines or vectors, now of animation or rest.

I can’t wait to see The Mindset in production. You really need one of these of your own – and so do I.

* ‘Faulty’ is my shorthand for a condition that has no specific name. From time to time I experience debilitating pains and petit mal seizures as phenomena along the migraine spectrum. There are two regions of my brain which are undergoing unexplained changes. Of the known triggers, long-tube fluorescent lights are the most common and, generally, the most easily avoided unless in exceptional circumstances where my accessibility requirements have been failed. The more constructive aspects of my condition include the experience of intense moments of extremely rapid mental processing, which generally arrive without warning and leave me utterly exhausted.

SLIDESHOW IMAGE: My composition of twelve cards taken at random from Sean Hogan’s The Mindset.