There are two key reasons why I’m voting ’Yes’ in this year’s Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum – and they’re both about trust:

I trust the process behind the Uluṟu Statement’s offer to all Australians.

I don’t trust future governments to respect that offer.

Let’s start with the positives.

The Uluṟu Statement from the Heart invites us all to walk together “in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.”

It is the culmination of decades of work spurred by two centuries of political advocacy by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Everything You Need to Know About the Voice – the new book by co-author of the Uluṟu Statement from the Heart Prof Megan Davis, and fellow Australian constitutional expert Prof George Williams AO – covers the history of this deeply considered, too-often frustrated work, and sets out a clear account of the process that created the Uluṟu Statement. Reading their book, we learn:

- The process was detailed, rigorous and comprehensive. Because “decisions needed to be made by those who had cultural authority”, each First Nations Regional Dialogue was structured “so as to require 60 per cent of invitations to the dialogue as traditional owners and elders, 20 per cent local Aboriginal organisations, and 20 per cent Aboriginal individuals such as Stolen Generations, youth or grandmothers.” This helped ensure “a robust representation of First Nations and community sentiment.” Around the structured Dialogues – which each followed the one consistent agenda – there were phone surveys, online consultations, written submissions, and community and public events. Some 200,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people were involved, with a clear majority supporting a Voice to Parliament, and mere constitutional acknowledgement the least supported of the reform priorities emerging from the Dialogues.

- Not only were the consultations extensive, but also, they formed the most representative constitutional process in Australian history. By proportion of the population, there was a higher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people involved in this process than the proportion of pre-federation colonial Australians involved in the conventions informing the 1901 constitution. The Referendum Council’s 2017 Report, cited by the authors, strongly emphasises the “unprecedented” nature of the Dialogues process as “the most proportionately significant consultation process that has ever been undertaken with First Peoples. Indeed, it engaged a greater proportion of the relevant population than the constitutional convention debates of the 1800s, from which First Peoples were excluded.”

- This work has taken a long-term and wholly bipartisan approach, advancing considerably during the prime ministerships of Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison. Former shadow attorney-general and shadow minister for Indigenous affairs Julian Leeser devoted a decade of diligent, collaborative to the Voice before moving to the backbench given Peter Dutton’s decision to end that bipartisanship, and Leeser remains a leading campaigner for a ‘Yes’ vote.

The careful work behind the Voice to Parliament proposal has had cultural oversight, integrity and transparency. It’s impossible not to trust in that. If only more policy processes were developed with such rigour.

And now to the negatives.

Unless it forms part of the constitution, it’s impossible to trust that a legislated Voice to Parliament can achieve the change Australia needs.

A uniform past experience has shown us that, when a body has been established by legislation alone, the next government can and will legislate it away, as Davis and Williams’ timeline shows:

- The 1958 Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement – which became the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the 1960s, and in the 1970s the National Aboriginal and Islander Liberation Movement – was disestablished in 1978;

- The 1973 National Aboriginal Consultative Committee was replaced by the 1977 National Aboriginal Conference, which was disestablished in 1985;

- The 1989 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission was disestablished in 2005.

Look into the reasons why and, on each occasion, there are accounts of deteriorating relationships between the relevant body and the government of the day.

While opposition leader Peter Dutton is calling for a Voice to Parliament that’s established only via legislation, it’s easy to see why. Especially given his choice to “re-racialise” the public debate. This kind of behaviour does not engender trust.

Further, last week’s leaked text message makes explicit what’s long been obvious: an ugly politicisation that refuses to engage with the offer made by the Uluṟu Statement. “We can’t win the election unless we defeat the Voice solidly, ie we need to defeat it to get to the election starting line”, wrote the unnamed Coalition MP.

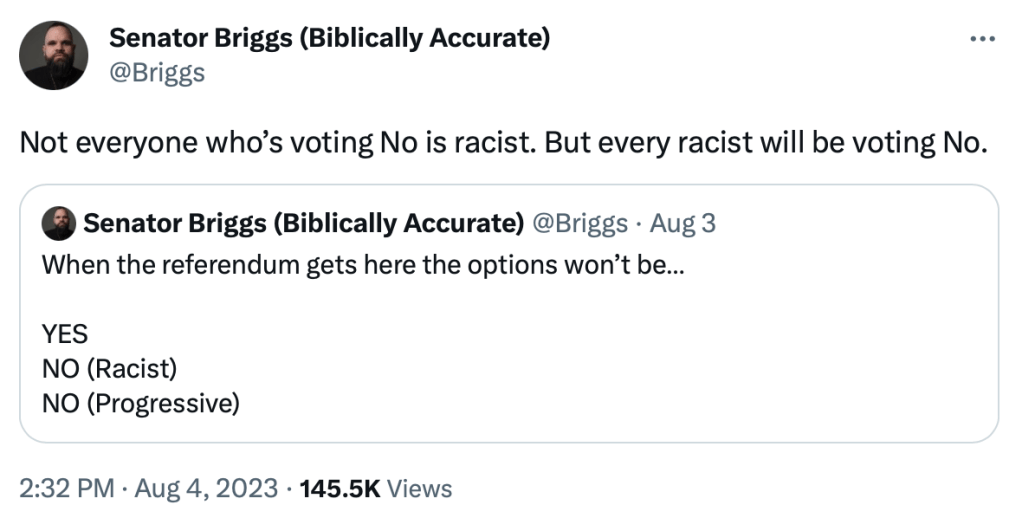

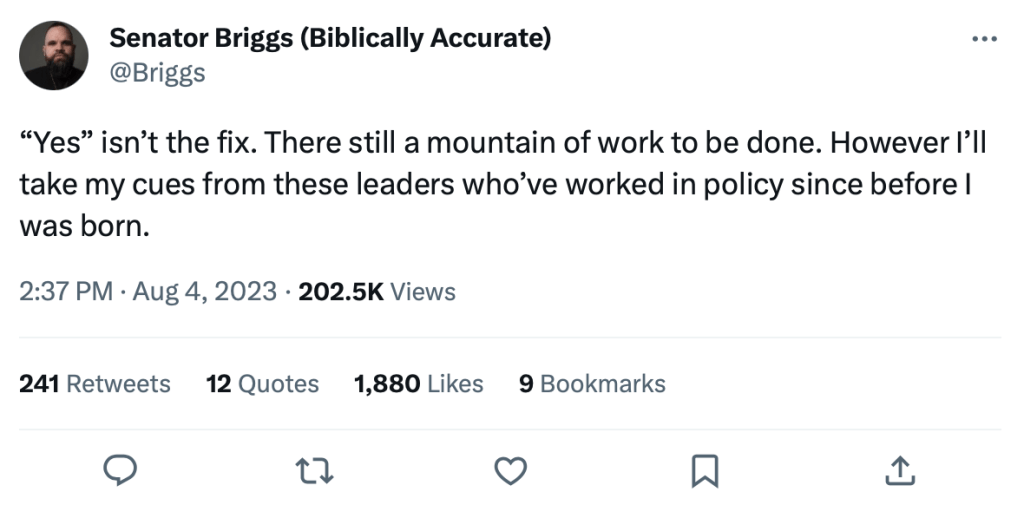

Disingenuous, dishonest arguments not made in good faith cannot be trusted. This ‘new shamelessness’, as I’ve argued elsewhere, must be called out.

Noel Pearson’s Garma Festival appeal to the 97% of Australians – the non-Indigenous population – who will ultimately decide this vote is critical: we are the beneficiaries of a nation premised on the violent dispossession of First Peoples’ land and culture whose impacts continue to be felt to this day. For meaningful, lasting change, Australia needs First Peoples to be heard on their terms. That self-determined approach isn’t going to emerge fully-formed and perfect, but it is going to change the nation for the better.

There’s only one way to achieve that: vote ‘Yes’.

And for anyone still resigned to letting the perfect be the enemy of the good, let’s give the final word to Briggs:

Join me tomorrow evening Tuesday 8 August 2023 at the Wheeler Centre for a discussion with Profs Megan Davis and George Williams about their new book Everything You Need to Know About the Voice.